Caregiving Challenges, Role Reversal of Parent and Child

When a parent reaches a stage of needing supervision and assistance, for the child caregiver, the roles of parent and child seem to reverse.

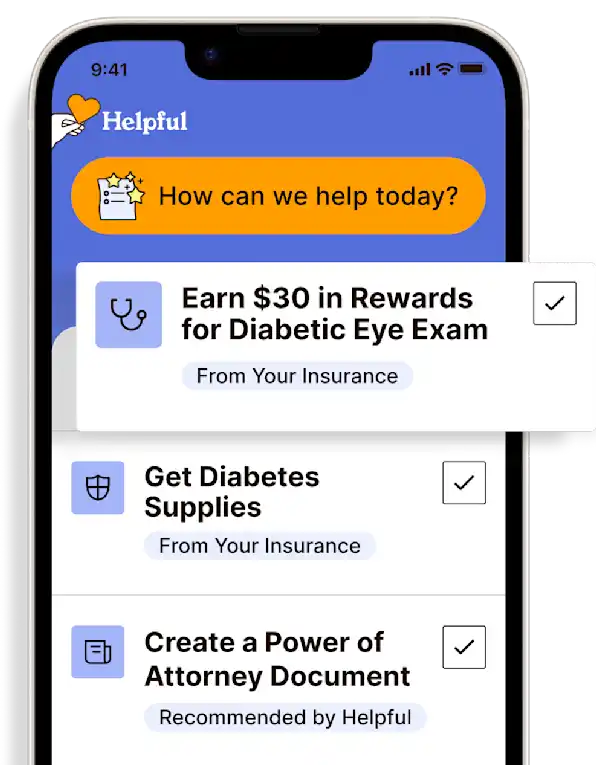

Get insurance benefits, legal documents, and medical records in one place

Helpful Highlights

Determining the form of role reversal you will occupy is essential.

Confusion and strain from role reversal greatly come from places other than the caregiving itself.

Just because you (and your parents) haven't been planning up to this point doesn't mean you shouldn't start planning now.

Recognizing and addressing your own negative feelings can ease the burden of caregiving.

What form of role reversal do you occupy?

Our parents' aging is not a sudden occurrence. It happens over a long period of time, though because our lives are also happening, when the time comes that our parents need assistance, we often feel unprepared, overwhelmed, and perhaps even guilty (for not paying closer attention). We quickly find ourselves in a role reversal, where we are now taking care of the people who took care of us.

For some, however, this role transition doesn't seem so rapid. Rather, the switch happens so gradually over time that it goes unnoticed. This doesn't necessarily mean they are better prepared to make difficult care decisions, though. Synonyms for unnoticed are overlooked, undiscovered, unrecognized, unseen, disregarded, and glossed over. Therefore, those who experience the transition slowly may be equally as uninformed in their care delivery as those who are thrust into it.

So, whether rapidly or slowly, we all end up in the same place, and we arrive there not having made a decision about what form of role reversal we will assume. This can cause confusion and strain.

Will I split the responsibility with siblings or other family members?

Will I be the primary caregiver?

Will my parent(s) move in with me when the time comes, or move into an assisted living facility or a nursing home?

Will I assume power of attorney?

Will I be responsible for their finances?

Will I oversee arranging in-home care?

Will I be the one performing nursing and medical tasks?

Will I be the one coordinating care (making appointments, communicating with providers, transporting, following up)?

Can I afford to cut back on work hours or quit my job?

What out-of-pocket costs will I bear in caring for them?

What are the effects on my own family?

As you'll find, there is much more to caring for aging parents than the caregiving itself, and their needs change as they continue aging and their chronic conditions progress.

Areas of role reversal confusion and strain

The sources of strain frequently aren't because the child is having to parent the parents. Role reversal brings a world of new and different caregiving responsibilities that we have not assumed before.

Driving privileges. This may not seem like a point of contention until you're the one having to limit or restrict your parent's ability to drive. You feel like your parents should just recognize when they should no longer be driving and give it up without fuss, not remembering that driving is independence and freedom and something your parents have been doing for probably 60+ years. Many people, instead of removing driving privileges, will compromise by riding with their parents or limiting travel to short distances during low traffic times. But the bottom line is, if they're not safe enough to drive whenever and wherever they want, they're likely not safe to drive at all. Driving conditions are unpredictable, even short distances to well-known destinations, and most accidents happen close to home. Any disruption can cause an issue when vision is poorer, reaction times are slower, and situational awareness and alertness aren't optimal. Unfortunately, there is no magic formula for persuading your parents to stop driving, and there are likely to be some arguing, insults, and hurt feelings no matter how it's handled.

ADLs, especially toileting and bathing. Activities of daily living (ADLs) are those activities essential for daily life - transferring, bathing, toileting, hygiene, dressing, and feeding. Of these, toileting and bathing can be particularly sensitive areas for you both. A parent needing assistance with wiping or being seen nude while bathing is not the same as it is for a child. With a child, you're doing something for them to teach them how to do it themselves. With aging parents, you're doing something for them that they have already learned to do but can't do anymore. One is imparting independence while the other one is withdrawing it. The vulnerability and embarrassment can be very mentally and emotionally impacting, and there aren't easy ways around it. (Note that the same applies to nursing and medical tasks.) For more on this, see Helpful Guide Bathing and Toileting Your Loved One.

Paying for long-term care. Most people do not have a plan to pay for long-term care, in the home or especially in a facility, and there's a good chance that you are your parents' long-term care plan. This is often the greatest source of strain because both in-home and facility care can deplete parents' savings and assets. And what happens when their money is gone? Do you seek assistance or do you spend your own money? If there is an opportunity now to get started on long-term care planning for your parents, do it. If that opportunity has passed, it may be best to consult with professionals who can help you manage what remains, as well as plan for the future, rather than trying to do it on your own. Financial planners, life planning counselors, and geriatric care managers, as well as aging parent support groups, can be good places to start.

Sibling rivalry. Parental care planning should involve all siblings. It is the hope that the joys and hardships of caring for parents will be shared among siblings. Unfortunately, situations arise where one or more siblings refuse to participate, or siblings perceive each other as taking advantage of parents for financial gain or other security (and this is actually true in some cases). When this occurs, it can be a good idea to involve a professional such as an elder care attorney, geriatric care manager, or licensed independent social worker. In order to be successful, planning must focus on the parents' needs, though the well-being of the children providing care - who can experience overwhelming emotions and a mountain of pressure - must also be considered. Professionals offer perspective and objectivity, as well as interpersonal and resource solutions.

Parental autonomy. Role reversal is like becoming a parent to your parents, but not exactly, because they're not children. Children are more manageable, we have more influence in their decisions and actions. Parents, however, provided they are not mentally incapacitated, have a mind of their own, maintain control over their assets, and sometimes (often?) ignore the advice of their children. The scenario is simple - they ask for your help, and you both agree to a plan, that your parents then ignore because they think they know better. And there is simply no recourse for that. They are free to make their choices and there are no consequences you can enforce to change the course of things. You must accept that you will likely have this whole conversation again in the future when things don't go as they expected. Hint: saying, "I told you so" doesn't work in your favor.

Power of attorney (POA). This designation doesn't behave like you see in shows and movies. Having a POA doesn't automatically grant someone absolute power over someone else. It is important to note that there are four - technically five - different types of POA, and each becomes active at different times and gives authority in different ways. There is a medical POA, financial POA, springing POA, and general POA. The technical fifth type is the durable or non-durable POA, which is applied to those above. It's also important to understand that the ability to act as a POA, regardless of the type, ends when that person dies. Planning for how property and other assets are divided and who receives them after passing requires a last will and testament.

Self-care takes a backseat. Deep respect and everlasting love of the aging parents sustain the adult child throughout the caregiving experience. However, you are likely stressed by your own developmental tasks of middle age. As mentioned, you are frequently unprepared for the role of caregiver, becoming a parent to your parents. This "sandwich" role has a potentially rocky effect. You, and your own healthcare providers, need to recognize and deal with the negative feelings you may have, such as resentment, anger, frustration, guilt, and demoralization (loss of confidence, enthusiasm, and hope). These emotions must be put into proper context if your mental and physical health, as well as the vital support you provide for your parents, are to be maintained.

Act one

With thorough planning and preparation, we can successfully role transition.

If you haven't already, save yourself a lot of frustration and inconvenience by gathering basic information about your parents: Social Security number, photo ID, health insurance cards, providers' names and contact information, a complete list of current medications (including non-prescription) and allergies, and accurate personal and family health histories.

Furthermore, if you don't know your parents' future care wishes and their financial situation, you need to find out now.

Refer to our Helpful series Take Care of Yourself and Prepare Yourself for loads of valuable information on where, when, and how to get involved in planning care for your aging parents.

RESOURCES

Darling, H.G. (2015, December 14). The ultimate role reversal: There are many issues to consider when children care for parents. Healthcare News. Link

Gilbert, S.M., Nemeth, L., Amella, E., Edlund, B., & Burggraf, V. (2018). Adult children and the transition of aging parents. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 39(5), 374-381. DOI

Hatfield, H. (2008, November 25). Role reversal: Caregiving for aging parents. WebMD. Link

Mandell, N. (2021, November 18). It could be time to talk with your Boomer parents about their money. Here are some tips. USA Today. Link

van Niekerk, T. (2020, October 6). Role reversal: Parenting your parent. LinkedIn. Link

Waterbury-Tieman, C. (2017, October 1). Heart-rending parent-child role reversal. NY Parenting.

Wendt, M. (2020, September 19). Parent-child role reversal. Union-Sun & Journal, Lifestyles: Senior Spotlight. Link

Yaffe, M.J. (1988). Implications of caring for an aging parent. Canadian Medical Association Journal (CMAJ), 138(3), 231-235. PMID, PMCID

No content in this app, regardless of date, should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.

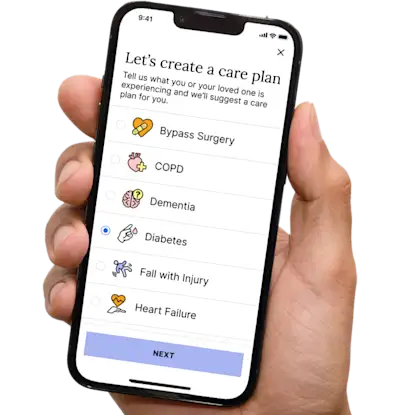

Get more support and guidance on insurance benefits, medical records and legal forms.

Helpful brings together your insurance benefits, legal documents, and medical records in one personalized place — so you always know what you have, and never have to search again.

Technology for Health Tasks. Mental Health for the Tough Stuff.

Helpful connects your medical records, insurance, and caregiving tasks automatically. And when you need more than logistics, a therapist is here to guide you.

In-Network and Covered

For Individuals, Couples and Families

HIPAA Compliant, Data Stays Private

Healthcare Tasks Simplified

From syncing records to spotting drug interactions, Helpful does the heavy lifting, turning complex health info into clear tasks and showing you benefits you can actually use, giving you clarity and control over your care.

In-Network Mental Health

Our licensed therapists are here to support you and your loved ones through stress, burnout, and life’s hardest moments, with an inclusive, compassionate approach that works with most insurance plans.

Create Legal Documents

Plan ahead by creating will, trusts, advance directives and more, that ensure your wishes are honored in the event you can’t speak for yourself -with Helpful guiding you every step of the way.