Breast Cancer Risk Increases as Age Increases

The reason mammograms start at age 40 and go until age 80+ is because those most threatened by breast cancer are older women.

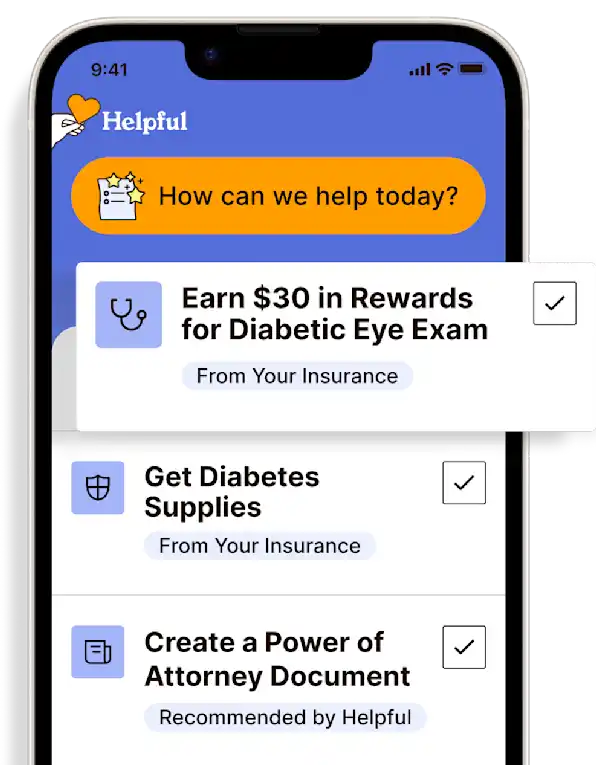

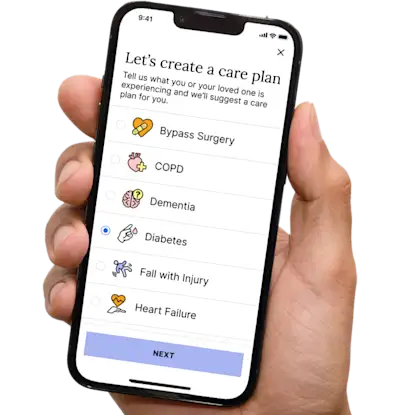

Get insurance benefits, legal documents, and medical records in one place

Helpful Highlights

The older a woman is, the more likely she is to get breast cancer!

Breast cancer survivors are more likely to experience depression and poorer quality of life, even years after diagnosis and treatment.

Strain increases among caregivers of older adults diagnosed with breast cancer.

It's important to note that men are not immune to breast cancer, especially as they age, and should be regularly communicating with their primary care provider about their risk.

Breast cancer and age

As with many other diseases, the risk of breast cancer rises as you get older. This is why it's important to continue getting routine breast cancer screenings (mammograms) as recommended or guided by a healthcare provider. Insurance providers cover this screening.

80% of women diagnosed with breast cancer are age 45 and older.

Most breast cancers are diagnosed after age 50, most at age 55 and older.

The median age for developing breast cancer is 63.

Rates are highest in women over age 70.

Screening in those aged 70 years and over continues to identify breast cancer at early stages and with improved survival.

Most women who die of breast cancer are older than 65.

Menopause and post-menopause significantly increase breast cancer risk.

The risk that a woman will be diagnosed with breast cancer during the next 10 years:

Age 40, 1 in 65 women

Age 50, 1 in 42 women

Age 60, 1 in 28 women

Age 70, 1 in 24 women

More age-related findings

If there is a silver lining, it is that while older women are at higher risk of getting breast cancer, outcome and survival are determined by the cancer type and comorbidities, not age itself, and otherwise healthy older women can and should be treated with the same standard as younger women.

This is important because there continues to be strong evidence that older women tend not to have their breast cancer managed in accordance with evidence-based practices.

They also often quit getting regular mammograms.

Breast cancer entities are continuously calling for older women to be specifically and effectively targeted by health promotion campaigns as the people most at risk of developing breast cancer and for older women to receive personalized care plans for treatment based on their individual circumstances rather than their chronological age.

Why does caregiving strain increase with breast cancer?

Breast cancer can lead to not only physical complications but also serious depression and severe emotional distress, especially during the first year after diagnosis. Depression and poor quality of life, however, are common among breast cancer patients even years after diagnosis and treatment. These conditions are particularly prevalent among older adults who already have other chronic illnesses, decline in function or mobility, and who may experience isolation and loneliness. This raises special challenges for caregivers regarding their physical health, mental health, cooperation with providers, adherence to therapies, and safety.

Depending on the type and stage of cancer, and age at diagnosis, the prognosis (outlook) could be poor, speeding up the need for palliative care and end-of-life considerations and planning.

Chemotherapy, and the addition of radiation treatment, can cause the person with breast cancer to feel very ill and weak, even triggering nausea, vomiting, and constipation or diarrhea. They can even cause cognitive decline (trouble with mental processes).

The persistence and rigor of cancer treatments increase mental and emotional burdens and burnout in the patient, manifesting in irritability, anger and upset, resistance and reluctance.

Moreover, this can cause decreased appetite and reduced intake of food and liquids in the individual, slowing healing and recovery, further weakening them and potentially causing other nutrition-related issues.

Likewise, depression has been proven to slow healing and recovery and contributes to already disrupted sleep patterns, diet, toileting, and energy level and amount of engagement. It can also contribute to confusion or other altered mental status.

Cancer treatments, chronic illnesses, and depression, especially when combined, cause significant fatigue. And, believe it or not, fatigue is a strong predictor of poor sleep.

If ya person has had a mastectomy (regardless of type), they are inevitably experiencing difficulty with the loss of a body part. For many, regardless of age, they feel they have lost a body part that defines their womanhood, motherhood, and/or self-defined beauty and attractiveness.

Some women cope with mastectomy well and adapt quickly, though research has shown that even they struggle with a sense of loss or body deformity for a period.

A prosthetic (breast implant) does not always help women positively adjust to the loss of a breast or breasts.

Loss leads to grieving and grief can revisit at any time through the remainder of life. The individual may return to grieving about the mastectomy and/or their body even if they have been fine for years.

What can I do to reduce strain?

Anticipation is key.

In other words, know as much as you can in advance.

Foremost, become familiar with the specific type of breast cancer - location, type of tumor, stage, aggression, invasiveness (surrounding tissues and metastasis), prognosis, and associated symptoms.

Also, get to know the recommended treatment - chemotherapy, radiation, surgery, or a combination.

Understanding this will help you know when and how you can best offer support. This knowledge allows you to plan in advance for:

Progression or remission of the cancer

Limitations due to pain and other symptoms, or medication side effects

Accommodations due to fatigue or weakness

Home modifications needed for safety and support (bathroom, bedroom)

Daily or weekly scheduling of in-home help and transportation (family, friends, hired)

Meal planning, shopping, and food prep according to recommendations as a result of treatment, as well as changes in appetite

Socialization or community support preferences (visitors and gatherings, support groups, church groups, or social clubs)

Timing of crucial conversations about future care planning (medical, financial, legal, end-of-life)

Continuous encouragement of open and honest expression of feelings, concerns, and questions

Your plan for self-care

Note that remission is no exception. Even if someone has been cancer-free for a long period, it's important to view cancer as an ongoing journey of recovery and understand the physical and mental aspects associated with being a breast cancer survivor, as well as the continued medical risks and residual effects of treatment.

RESOURCES

Ip, E.C., Cohen-Hallaleh, R.B., & Ng, A.K. (2020). Extending screening in "elderly" patients: Should we consider a selective approach? Clinical Breast Cancer, 20(5), 377-381. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clbc.2020.03.009

Lange, M., Heutte, N., Rigal, O., Noal, S., Kurtz, J-E., Levy, C., Allouache, D., Rieux, C., Lefel, J., Clarisse, B., Veyret, C., Barthelemy, P., Longato, N., Castel, H., Eustache, F., Giffard, B., & Joly, F. (2016). Decline in cognitive function in older adults with early-stage breast cancer after adjuvant treatment. Oncologist, 21(11), 1337-1348. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2016-0014

Meresse, M., Bouhnik, A-D., Bendiane, M-K., Retornaz, F., Rousseau, F., Rey, D., & Giorgi, R. (2017). Chemotherapy in old women with breast cancer: Is age still a predictor for under treatment? Breast Journal, 23(2=3), 256-266. doi: 10.1111/tbj.12726

Odle, T.G. (2020). Breast cancer in older adults. Radiologic Technology, 92(1), 53M-70M. PMID: 32879026

Overcash, J., Tan, A., Patel, K., & Noonan, A.M. (2018). Factors associated with poor sleep in older women diagnosed with breast cancer. Oncology Nursing Forum, 45(3), 359-371. doi: 10.1188/18.ONF.359-371

Overcash, J., Johnston, M. Sinnott, L.T., & Williams, N. (2022). Influence of patient functional status and depression on strain in caregivers. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, 26(4), 406-412. doi: 10.1188/22.CJON.406-412

Paek, M-S., Wong, S.S., Hsu, F-C., Avis, N.E., Fina, N.F., & Clark, C.J. (2021). Depressive symptoms and associated health-related variables in older adult breast cancer survivors and non-cancer controls. Oncology Nursing Forum, 48(4), 412-422. doi: 10.1188/21.ONF.412-422

Tesarova, P. (2013). Breast cancer in the elderly - Should it be treated differently? Reports of Practical Oncology and Radiotherapy, 18(1), 26-33. doi: 10.1016/j.rpor.2012.05.005

No content in this app, regardless of date, should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.

Get more support and guidance on insurance benefits, medical records and legal forms.

Helpful brings together your insurance benefits, legal documents, and medical records in one personalized place — so you always know what you have, and never have to search again.

Technology for Health Tasks. Mental Health for the Tough Stuff.

Helpful connects your medical records, insurance, and caregiving tasks automatically. And when you need more than logistics, a therapist is here to guide you.

In-Network and Covered

For Individuals, Couples and Families

HIPAA Compliant, Data Stays Private

Healthcare Tasks Simplified

From syncing records to spotting drug interactions, Helpful does the heavy lifting, turning complex health info into clear tasks and showing you benefits you can actually use, giving you clarity and control over your care.

In-Network Mental Health

Our licensed therapists are here to support you and your loved ones through stress, burnout, and life’s hardest moments, with an inclusive, compassionate approach that works with most insurance plans.

Create Legal Documents

Plan ahead by creating will, trusts, advance directives and more, that ensure your wishes are honored in the event you can’t speak for yourself -with Helpful guiding you every step of the way.